Letter from home

Originally published in Acoustic Guitar magazine, July 1997

Dear Readers,

Lila with her uke.

It all started innocently enough, in a quiet domestic scene a few nights ago. I was sitting there on the bed trying to iron a few wrinkles out of a guitar arrangement when Lila, my two-year-old daughter, barreled into the room, stopping just short of knocking me and my guitar flat on my back. With hardly a pause, she pulled the pick out of my hand and, after twirling it a few times in her fingers, gave the strings a light strum while I was still holding an E minor chord. Her face lit up at the sound of the ringing strings, so she strummed them again—a little harder this time. And again, with a delighted little squeal, before she put the pick down and launched into one of her acoustic thrasher interludes, slapping at the strings with an abandon that makes Michael Hedges look like a complete cream puff.

I started making a little chord circle with Em, G, and A, following her erratic rhythm and adding a few little left-hand ornaments of my own. This tandem performance kept us occupied for a few minutes, but soon she wanted to go get her own “gigi” (pronounced “jeejee”)—a plywood ukulele that I bought for her last year. I had attached a bright-colored shoelace onto it to function as a strap, and with a little help she got the uke in position over her belly and swept her fingers across its nylon strings. I knew what was coming next and put the strap on my guitar to get ready, as she strutted out of the bedroom, strumming the uke and bouncing up and down with each step while singing “Frère Jacques.” I began adding my guitar to the musical mayhem, joining the procession through the kitchen and then around to the living room sofa, where we recruited Mommy-o, as she’s known around here, to join the party.

I’m not sure how long we proceeded through the apartment like this, like a bunch of Mardi Gras revelers in the wee hours, but it lasted for at least a few choruses of “Frère Jacques” and plenty long enough to make me forget whatever half-serious guitar project I was working on when Lila interrupted me.

Ever since Lila transformed herself from a babbling infant into a walking, talking human being, music has been erupting like this in our home on a regular—or, rather, entirely irregular and unpredictable—basis. I marvel at the way music flows into and out of her, a freewheeling mixture of learned and improvised words, familiar melodies and joyful noise, created without a trace of self-consciousness. The same could be said of her (or any child’s) drawing or dancing: it’s artistic expression that’s never been encumbered by the notion that it’s an artistic expression. To her, the singing and parading is just part of life, and so it’s become part of mine too—an unexpected gift of parenthood, and a poignant reminder of how this kind of social, spontaneous music making has been too absent from my life for too long.

Lila’s music is so pure and vital, I sometimes wonder, what could possibly prevent it from flowering throughout her life? The unfortunate answer is that there are many ways in which the culture she will grow up in discourages and devalues this kind of down-home music making. Music in other forms, of course, is everywhere: it fills our CD rack, serenades us from the radio and TV, tries to placate us while we’re on hold or stuck in an elevator.

The products of music surround us, but the production of music for no commercial purpose—for no purpose other than the giddy entertainment of a family of three—is something of an endangered species.

The products of music surround us, but the production of music for no commercial purpose—for no purpose other than the giddy entertainment of a family of three—is something of an endangered species.

I know it hasn’t always been this way, but to me, the images of families circled around the upright piano after dinner are as distant as those of hoboes strumming in an open boxcar. The reality for me in my family and the pocket of New Jersey suburbia in which I grew up was that music was something that came primarily from records and the radio, and occasionally from large-arena concerts (essentially a reproduction of the records). I learned to play music from the records, not from any family or community tradition or from in-person instruction. From the beginning, my reference point was the professionals—the pop stars and slick studio cats, captured in a medium made to sell. Naturally enough, this was the framework in which I considered my own music making as it developed: Was it good enough to get gigs? Could I land a record deal someday? There’s nothing wrong with these aspirations, but over time I’ve come to realize how little any of this has to do with parading around the house singing “Frère Jacques” with my daughter, how the primacy of professionalism subverts the music made just for the hell of it.

There are so many ways in which this reality affects my life as a mostly amateur, occasionally gigging musician today. From the singer-songwriter giants of the ’70s I inherited the desire to write songs; eventually this became my musical mission, so that much of the huge repertoire of covers that I performed as a teenager has faded from my memory. That focus has given me a large body of original music, much of it arranged with my brother or our band, some of it captured on tape with varying degrees of success. I love that creative enterprise, but more and more I regret the absence of any repertoire that can be shared with others—a body of folk songs, fiddle tunes, jazz standards, whatever.

I know scores of other musicians who feel similarly cut off from each other because we’ve each grown up with our own personal selection of recording artists (in the years since I came of age musically, this situation has become more and more aggravated, as audiences—and the radio formats that target them—have continued to splinter and subdivide). When we attempt to jam together, we either follow along as another person plays a song we don’t really know, we collectively fumble through a couple of Beatles or Grateful Dead songs, or we default to the old faithful: 12-bar blues in E. Christmas songs are about the only widely known repertoire (not counting TV jingles and theme songs), but those are in circulation for only about one month of the year, and even then, the singing falters after the first verse.

Too many people have become too accustomed to being passive consumers of music, and it takes a real perceptual leap to see yourself as someone who can make music too.

A good deal of blame for this situation can be laid at the feet of recordings—those miraculous discs that allow us to travel at the push of a button from 60-year-old Delta blues to techno dance grooves to Tuvan throat singing. The variety, quality, and quantity of recorded music available today is astounding, but there’s a serious downside: too many people have become too accustomed to being passive consumers of music, and it takes a real perceptual leap to see yourself as someone who can make music too. Even for those of us who do manage to make the transition from listeners to players, that thing called product still rules; our dreams are first and foremost of having a shiny disc with our own name on it. Performing is an afterthought, mainly worth doing in support of a CD release, or at best it’s something that would be fun and rewarding if only the club scene weren’t so dismal. As a result, many of us pour our hearts into tape machines without ever really experiencing the growth and connection that comes only from laying it on the line in front of an audience, over and over again, testing and learning. And who can blame us? We’re only focusing our efforts on exactly what our society tells us we should focus on.

In the end, it’s not the pro or semipro musicians who suffer most from the tyranny of the shiny disc—they’re the ones who are most likely to engage in music in all settings, formal and informal, gigs and jam sessions. It’s what they do. The people who really lose out are the ones who just play a little music on the side, or who maybe don’t play any music at all but have always wanted to. They’re the ones who are most likely to feel that their guitar playing or singing isn’t important because there isn’t shrink-wrap or a bar code on it—and if it’s not important, why share it? These are the people who have the most to gain from knocking music off its professional pedestal, claiming it for their own, and letting it run loose in their homes.

My wish for my daughter is that she never lose touch with the communal spirit of music, and I cradle the same wish for myself. I know there are many pockets out there where people come together to play music for no reason other than to celebrate the moment and their companionship—campfire jams at festivals, folk society get-togethers, churches, homes where music comes out of soundholes as well as speakers. I’d like to find more of those places; they’re a critical reminder of why human beings started banging on sticks and wires to make noise in the first place. Collectively, we’ve got to make the effort to nurture those special musical spaces where they exist or create them where they don’t, grab our guitars, swallow our self-consciousness and fears about measuring up, and join in the jam.

As for me, I think rocking out on a couple of choruses of “Frère Jacques” right here at home is a pretty good place to start.

Best,

Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers

Postscript 2019

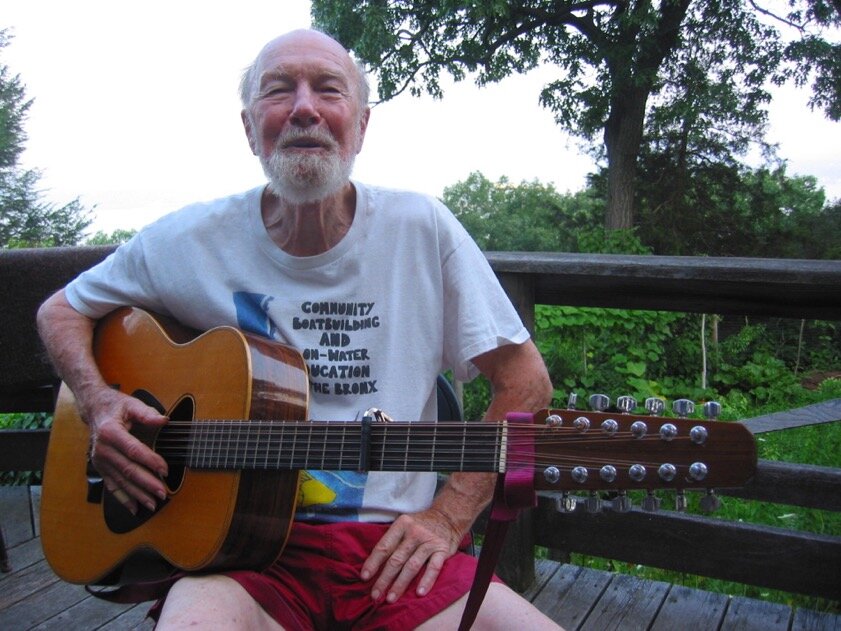

I wrote this reflection for Acoustic Guitar magazine more than 20 years ago. I decided to dig it out of the archive not just because of the personal topic and the sweet memories it captures, but because of a postcard I received about it from none other than Pete Seeger—which initiated an ongoing correspondence, several interviews, and eventually a visit to his home.

Postcard from Pete Seeger, 1997.

All this came back to me because I just published a feature (again in Acoustic Guitar, in the November/December 2019 issue) about Pete’s correspondence with musicians and the huge impact that his advice and encouragement made in the lives of so many. You can read that story here. In many ways, inspiring others to create and participate, whether in music or their communities, was his life’s work. Here are a few photos I took of Pete that day.

Pete Seeger with his Bruce A. Taylor 12-string guitar, on his deck in Beacon, New York, 2006. Photo by Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers.

Pete Seeger plays his iconic five-string banjo.

It’s interesting to revisit my “Letter from Home” more than two decades later and consider how things have changed—or stayed the same. On the family front, Lila wound up learning violin through school orchestra programs and still plays occasionally. At the time I wrote that article, I had a full-time job as editor of Acoustic Guitar and a busy home life as a new parent, so performing naturally took a backseat. As my kids grew older (Lila was joined by a brother five years later), I became much more publicly active with music, onstage and off. Playing and teaching music is integral to my life and livelihood these days.

I chuckled to read the reference in the article to the dream of landing a record deal, because that whole idea has become irrelevant for someone like me. I have put out a bunch of records, but like so many working musicians, I am fully independent. At the grassroots levels of the music business, DIY is the only viable way.

The core idea of this letter, though, remains more true than ever. As it has become easier and easier to access music 24/7 from devices that are always at hand, more and more people, I’d venture, settle into being consumers of music and never even consider making their own.

That is a real loss, as Pete knew so well—not just for music but for our society. It’s up to all of us to raise our voices and see what kind of sound we can make together.

—JPR