Chord progressions in major keys

Adapted from The Complete Singer-Songwriter

Chord progressions are the engine of songwriting. The melodic or lyrical hook may be what lodges in people’s heads, but the chord progression is what makes everything move.

By itself, a chord is just a static thing—a few notes stacked together—but a group of chords arranged artfully in a progression creates a little harmonic journey. There’s a kind of magic in a great chord progression, a mix of soothing familiarity and thrilling surprise that has emotional power even without the melody and lyrics.

So every songwriter needs to be fluent with chord progressions, but the process of figuring out which chords to use and how to sequence them can be mystifying. You can create progressions by randomly trying chords, but with a basic theoretical understanding of chords and keys, you can zero in much more quickly on good options to try in a progression—and become a more productive and versatile songwriter overall.

Chords by number

The secret to understanding chord progressions is identifying chords in a progression by number—not by the letter names of the chords. This is the idea at work at a jam session when someone kicking off a song says, “It’s I–IV–V in G,” rather than, “The chords are G, C, and D.” What these numbers do is describe the function of the chords no matter what key you’re in; a I–IV–V in D works the same as a I–IV–V in G.

When you’re thinking of chords by number, you can quickly change a song’s key, pinpoint what’s happening in a cool chord sequence, or make connections between songs. You understand the musical logic, which in turn allows you to put that logic to work in your own songwriting.

This numbering system is based on the seven notes in the major scale, also called scale degrees. Using notes from the scale, we can build a chord on on top of each scale degree and arrive at the diatonic chords—a family of chords that occur naturally in any key. Even if you’re not familiar with any of this theory, your ears recognize how diatonic chords fit together, because you’ve heard them at work in songs your whole life.

For a full explanation of the number system, see The Complete Singer-Songwriter. For our purposes here, let’s cut to the chase and say that in a major key, the diatonic chords are as follows:

I ii iii IV V vi viiº

The Roman numerals indicate the scale degree the chord is built on, as well as the type of chord: major chords are uppercase, and minor and diminished chords are lowercase (diminished chords are indicated with ° or dim). The I is the tonic or root chord and also the name of the key. No matter what key we’re in, the I, IV, and V chords are major; the ii, iii, and vi are minor; and the vii° is diminished.

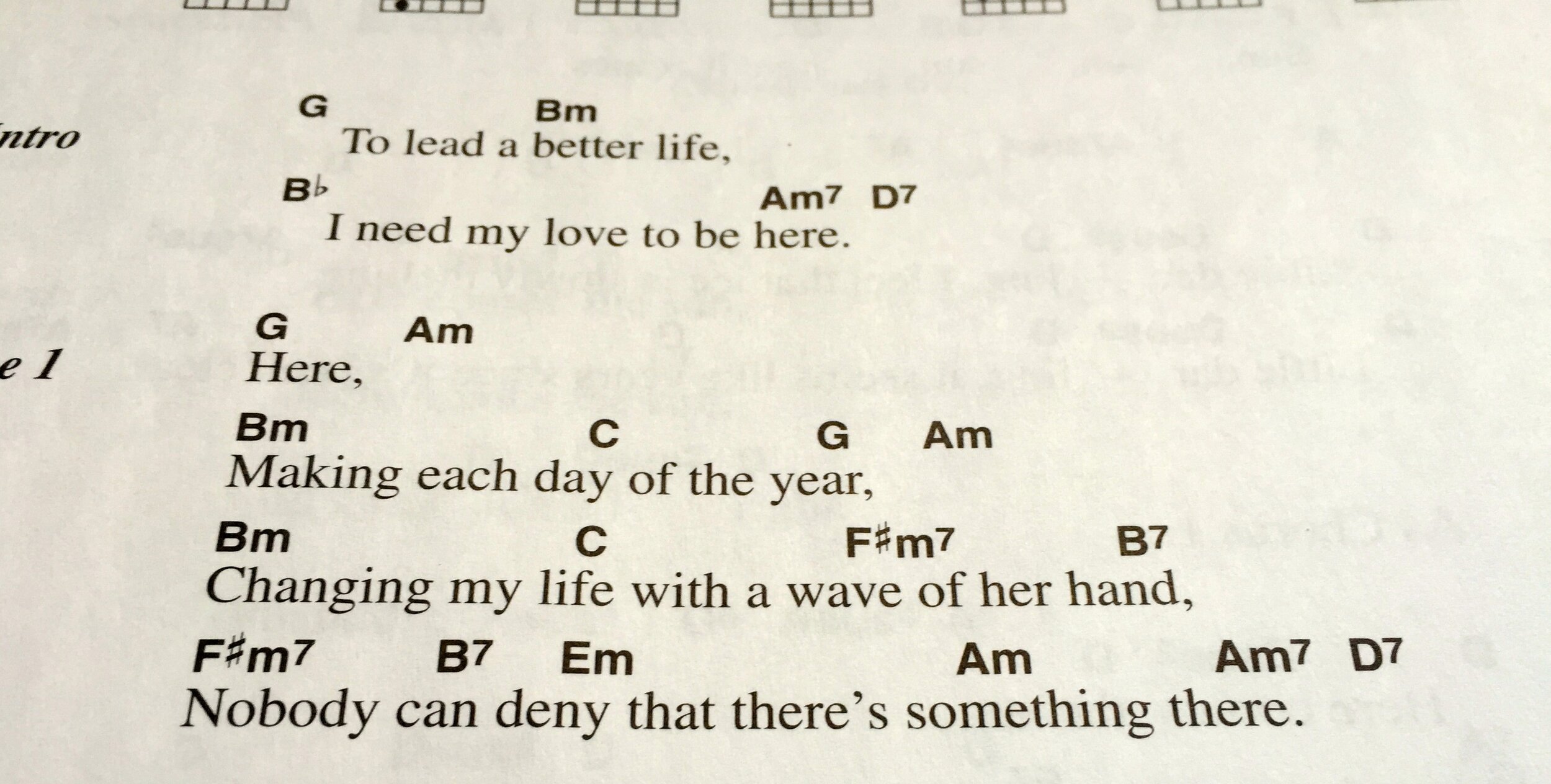

So in the key of G major, for instance, the diatonic chords are:

G (I) Am (ii) Bm (iii) C (IV) D (V) Em (vi) F#dim (viiº)

In practice, what this means is that a straightforward song in the key of G might use only this set of chords. In fact, many popular songs include only three or four of the diatonic chords. Out of the universe of chords, songwriters are often working with just a handful of options.

Let’s use the number system to run through a few diatonic chord progressions in major keys, starting with the most basic. (Note to guitarists: a guitar-specific presentation of some of this material, with tab and video, is available in the Acoustic Guitar Guide titled Songwriting Basics for Guitarists.)

Just the I

Some songs don’t change chords at all—they simply hang out on the I (often, a bluesy I7 chord) and rely on the melody, groove, and lyrics to maintain musical interest. Here are a few one-chord examples; listen in the accompanying playlist.

“Mannish Boy,” Muddy Waters

“Run through the Jungle,” Creedence Clearwater Revival

“Chain of Fools,” Aretha Franklin (Don Covay)

“Loser,” Beck

“Coconut,” Harry Nilsson

“Joy,” Lucinda Williams

“Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” Sly and the Family Stone

“Yup,” David Rawlings

Even though these songs don’t change chords, the accompaniment still moves—often with a bass line or riff.

My own song “Sycamore Tree” stays on the I chord the whole time—even in the eight-minute live version included in the playlist. The focus stays on the story, the beat, and the interplay of drums, bass, and guitar.

I and V

If a song adds just one more chord to the I, chances are it’s the V. The move from V to I is fundamental—once the home-base I chord is established and a song goes to the V, our ears want it to resolve to the I. Rocking between I and V is more than enough tension and release on which to build a song, as proven by these examples.

“Jambalaya,” Hank Williams

“Give Peace a Chance,” John Lennon

“Iko Iko,” the Dixie Cups

“You Can Never Tell,” Chuck Berry

“Man Smart, Women Smarter,” King Radio

“Pay Me My Money Down,” the Weavers

“Achy Breaky Heart,” Billy Ray Cyrus

I and IV

A surprising number of songs use only the I and IV; here are notable examples. Think of the I and IV as the “amen” chords in a hymn: you sing “ah” on the IV and resolve to the I on “men.”

“Born in the U.S.A.,” Bruce Springsteen

“Everyday People,” Sly and the Family Stone

“Paperback Writer,” the Beatles

“Use Me,” Bill Withers

“Unknown Legend,” Neil Young

“Changed the Locks,” Lucinda Williams

“Lively Up Yourself,” Bob Marley

“Feelin’ Alright,” Traffic (also Joe Cocker; written by Dave Mason)

“I’ll Take You There,” Staples Singers (Al Bell)

“The Walls of Time,” Peter Rowan

“Heroin,” Velvet Underground

I, IV, V

Add the IV chord to the I and V, and you’ve got the chord trinity behind countless songs in all sorts of styles—folk, blues, rock, country, bluegrass, reggae, and beyond. When people say all you need are three chords and the truth, these are the chords they mean. The I, IV, and V can appear in any order, as you can see in these songs.

“La Bamba,” Richie Valens:

I IV V

“Helpless,” Neil Young

“Black Boys on Mopeds,” Sinead O’Connor:

I V IV

“This Land Is Your Land,” Woody Guthrie:

IV I V I

Here are a few other I–IV–V examples in various genres:

“I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” U2

“Ring of Fire,” Johnny Cash

“Three Little Birds,” Bob Marley

“Man of Constant Sorrow,” Ralph Stanley

“Johnny B. Goode,” Chuck Berry

“I Fought the Law,” the Clash

“How Long Till It’s Too Late” is one of my own I–IV–V songs. The guitar solo stays put on the I.

Take vi

Venturing outside the I, IV, and V, the next diatonic chord you’re likely to encounter is the vi. Many songs move between the I and vi—a smooth change because the chords have two of their three notes in common, as you can hear in “Shout.”

“Shout,” Isley Brothers

I vi / bridge I IV

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s version of “Pastures of Plenty” uses the same chord combo: primarily switching between I and vi, and occasionally subbing in the IV.

“Pastures of Plenty,” Ramblin Jack Elliott (Woody Guthrie)

I vi

I IV

One of the templates of early rock ’n’ roll is I–vi–IV–V, used most famously in “Stand By Me.”

“Stand By Me,” Ben E. King (with Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller):

I vi IV V

The same sequence is heard in the Beatles’ “Octopus’s Garden” and the Police’s “Every Breath You Take” (in which the chords are dressed up with ninths for a jazzier sound). Reorder these four chords and you get the progressions for tons of other songs. Note that the following are excerpts, not complete chord charts—these songs have additional sections.

“Octopus’s Garden,” the Beatles:

chorus I vi IV V

“Every Breath You Take,” the Police:

I vi IV V vi / I vi IV V I

“With or Without You,” U2

“The Story,” Brandi Carlile:

I V vi IV

I–V–vi–IV is the ubiquitous progression in pop music famously featured in the “4 Chords” video by Axis of Awesome.

“Take Me Home, Country Roads,” John Denver:

chorus I V vi IV / I V IV I

“Let It Be,” the Beatles:

verse I V vi IV / I V IV I

The verse of my song “Turn Away” is built around a change between vi and I.

vi I vi I

vi I V IV

By shuffling around the I, IV, V, and vi, changing how long you hold each chord, and trying different rhythmic feels, you can cover a tremendous amount of songwriting territory.

The ii and iii

By adding the ii and iii chords to your songwriting palette, you can create seemingly infinite progressions. Here are some examples.

The first three use the ii in conjunction with the IV and V.

“Friend of the Devil,” Grateful Dead:

verse I IV I IV

chorus V ii V ii V

“Don’t Let Me Down,” Beatles:

verse/chorus I ii I ii

bridge I V I

“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” Bob Dylan:

I ii IV I

The Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses” uses both the ii and iii in the verse.

verse iii I iii I / ii IV V I V IV

Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” ascends the diatonic chords like a ladder: I–ii–iii to a quick IV–V.

I ii iii IV V or I ii iii ii

Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” uses a similar pattern: the verses start with I–ii–iii–IV–V, hang for a couple lines on IV–V, and then go right back down, IV–iii–ii–I.

verse I ii iii IV V 2x / IV V IV V

IV iii ii I 2x / ii IV V

In these examples you can see some common functions of the ii and iii:

ii leads to V or IV

iii leads to IV

The vii°

So what about the diatonic vii° chord, which is conspicuously absent from the above examples?

The vii° is used infrequently in contemporary songwriting, so I’m opting to skip over it for the purposes of this intro lesson. In practice, songwriters in folk/country/rock/pop are much more likely to reach for the nondiatonic bVII, which has its root a whole step (two frets on the guitar) below the I. Here are the bVII chords in five common keys.

I bVII

C Bb

A G

G F

E D

D C

Learn more about the bVII in this lesson.

Dig deeper

With a good handle on these diatonic chords, you are ready to roll for writing in major keys—and you’re also primed for our next topic, chord progressions in minor keys.

For more on understanding chord progressions, see The Complete Singer-Songwriter.