Understanding song form

Adapted from The Complete Singer-Songwriter.

Beneath all the nuances of melodies and lyrics, most songs are built from the same basic parts—some kind of sequence of verse, chorus, bridge, and so on. For writing a song, learning to play someone else’s song, or communicating with other musicians, being able to identify these parts and patterns is an essential skill.

Let’s take a look at common song forms used in rock, country, folk, and pop, and consider how their components function and fit together. Check out the Spotify playlists for some classic examples.

Verse only

The simplest song form has only one section, the verse—the same melody and chord progression repeats through the entire thing while the words change. This is the traditional ballad form, as used in these songs:

Pretty Polly

The House Carpenter

I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow

Promised Land (Chuck Berry)

All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan)

1952 Vincent Black Lightning (Richard Thompson)

Jerusalem Tomorrow (David Olney)

As these examples suggest, the verse-only form is a great storytelling vehicle (murder and tragedy are optional but recommended). Since the music isn’t changing, listeners can focus on the unfolding narrative. So you might consider writing in this form when the story is the most important aspect of the song.

Verse with refrain

Some songs use the verse-only form, but each verse ends (or sometimes begins) with the same phrase or line—the refrain. The refrain usually contains the song’s title too, as in:

I Walk the Line (Johnny Cash)

The Times They Are A-Changin’ (Bob Dylan)

Bridge Over Troubled Water (Simon and Garfunkel)

California Stars (Woody Guthrie/Wilco/Billy Bragg)

The line can be a little blurry between a refrain and a chorus (covered next). The difference is that a refrain is shorter—usually just one line of lyrics—and doesn’t feel like a separate section of the song. It’s more like the conclusion of the verse. The verse-refrain form retains the storytelling power of using verses only, while adding the benefits of repetition for sticking in a listener’s memory.

A song with a verse/refrain may also include a bridge (see below for more about bridges). Two examples on the playlist are:

Still Crazy After All These Years (Paul Simon)

Dear Prudence (Beatles)

In my own repertoire, I use the verse/refrain form in the song “Here.” I originally wrote “Here” a cappella and wanted to keep the whole song as simple and unadorned as possible, with just a touch of repetition from the “I am here / You are here” refrain at the ends of the verses. The instrumental is a solo guitar rendition of the verse.

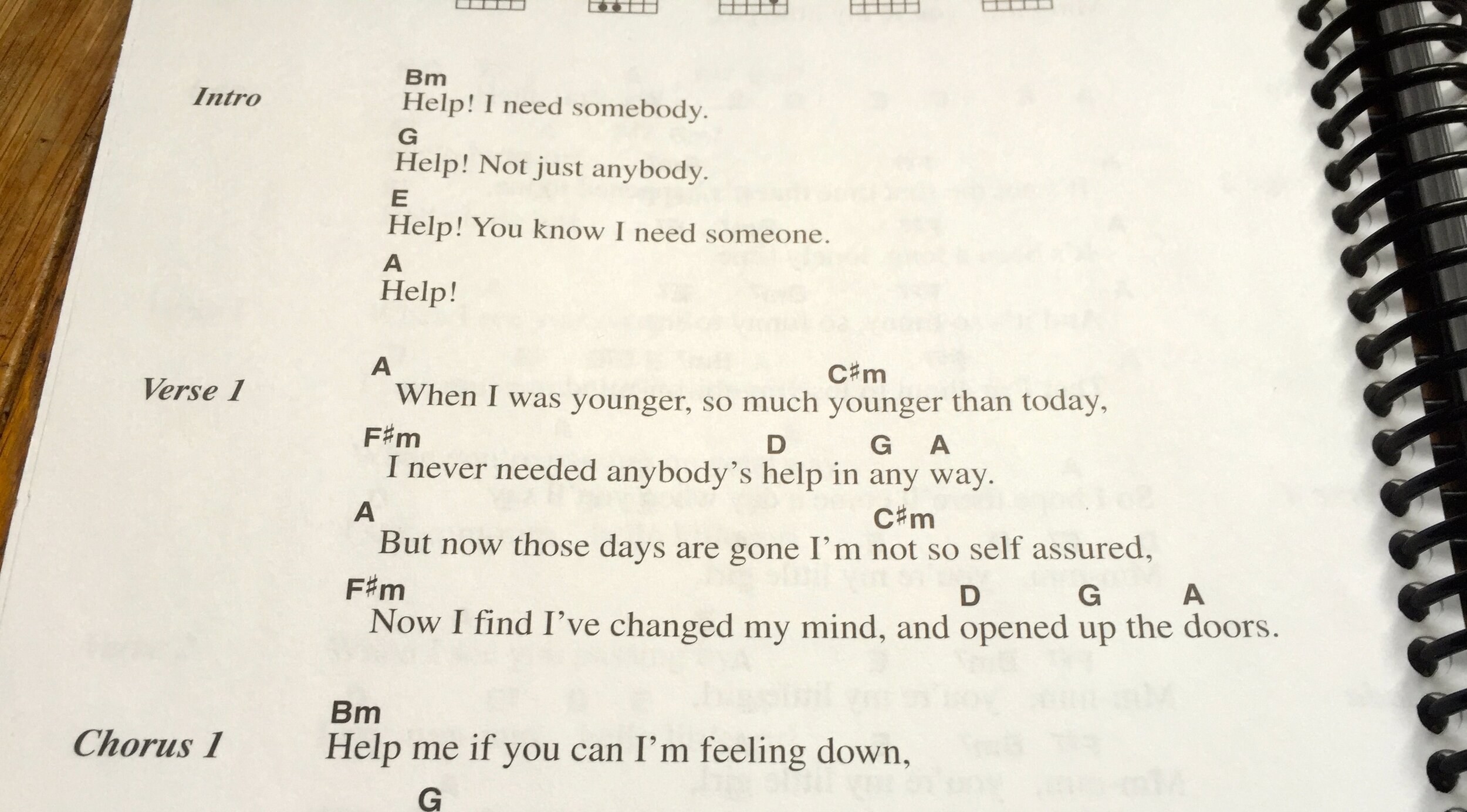

Verse and chorus

You know the chorus when it hits: it’s the sing-along and raise-your-lighter part, with the same words each time and almost always the song’s hook/title, in a distinct section that repeats typically three or four times. While the verses carry the story forward, the chorus nails the song’s main theme, image, or feeling.

The simplest type of chorus uses the same music as the verse, as in:

This Land Is Your Land (Woody Guthrie)

Will the Circle Be Unbroken

You Are My Sunshine

Gillian Welch’s “Everything Is Free” and John Prine’s “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” also use the same chords and virtually the same melody for the verse and chorus. Usually, though, the chorus brings a change of melody—often rising into a higher register, as in the other selections here.

Beck’s “Loser” follows a pattern used in lots of pop songs: rapped verses and a sung chorus.

My own “Sycamore Tree” has spoken verses and a sung chorus.

It’s tougher to tell a complex story in a verse-chorus song, simply because the repeating chorus takes up much of the space. Instead, the strength of the verse-chorus form is capturing a feeling . . . and then lodging in listeners’ heads.

Verse and bridge

Some songs have a second contrasting section, with a different melody and chords than the verse, that doesn’t feel like the focal point of the song the way a chorus does. It’s more like a short diversion from the verses, and it’s not repeated over and over—it comes up once or maybe twice. That contrasting section is the bridge, also known (especially on the eastern side of the Atlantic) as the middle eight.

Songs that use only a verse and bridge often have an old-fashioned sound, because the 32-bar AABA form was standard in Tin Pan Alley songwriting. Examples include:

Over the Rainbow (Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg; the bridge begins, “One day I wish upon a star”)

Yesterday (Paul McCartney; “Why she had to go”)

Imagine (John Lennon; “You may say I’m a dreamer”)

These songs use the AABA form but also incorporate refrains—each A section ends with the title phrase:

What a Wonderful World (George David Weiss and Bob Thiele)

Dream a Little Dream of Me (Fabian Andre, Wilbur Schwandt, and Gus Kahn)

If I Knew (Bruno Mars)

In terms of the music, the bridge often modulates to a new key, changes up the rhythmic feel, or introduces a melodic idea quite different from the verse.

The Grateful Dead’s “Althea” is a much longer song than the above examples, but still has only verses and one bridge (“There are things you can replace”).

My own “Tiny Song” has a somewhat different take on the AABA form. The song opens with two verses, and in the extended bridge the chord progression stays the same but the melody and instrumentation change with the introduction of drums and saxophone. Then the song strips back down to guitar and voice for a final verse.

For more on how to write a bridge, see this lesson from Acoustic Guitar.

Verse, chorus, and bridge

Using a three-part form of verse, chorus, and bridge opens up a lot of possibilities for songwriting. With three parts, the verses move the story along, the chorus delivers the hook, and the bridge gives listeners a break from the predictable back and forth of verse/chorus. Many songs use a structure like verse-chorus/verse-chorus/bridge/verse-chorus, where the bridge provides a refreshing change before the final verse and chorus.

The Lennon and McCartney catalogue is chock full of clever uses of the verse-chorus-bridge (I mean middle eight) form. For instance:

“I Want to Hold Your Hand” follows the verse-chorus/verse-chorus/bridge/verse-chorus form mentioned above and then adds on one more bridge/verse-chorus (the bridge begins, “And when I touch you”).

“Eight Days a Week” uses the exact same form (with the addition of an intro and outro—more on those below), as does “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.”

Verse-chorus-bridge is probably the most common form in my own songs. In the example in the playlist, “Any Other Way,” the bridge (“Sunday I am on my knees”) pauses the driving rhythm for a moment of reflection unlike anything else in the song.

Prechorus

Especially in the realm of pop/rock, songwriters often write a prechorus, a short section of four bars or so that sets up the chorus and uses the same words/music each time.

Think of Tom Petty’s “Refugee”; the prechorus goes: “It don’t make no difference to me...” and builds anticipation for the chorus: “You don’t have to live like a refugee.”

Similarly, in Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary,” the prechorus starts with “Big wheels keep on turning” and leads into the chorus: “Rolling on the river.”

To pick a few examples off the more recent pop charts, Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” has a prechorus beginning with “We’ve come so far,” and Lorde’s “Royals” has an extended prechorus starting with “But every song’s like gold teeth, Grey Goose, trippin’ in the bathroom.” In both cases, these repeating sections launch into the big chorus and, you guessed it, the title/hook.

My song “Stop, Drop, and Roll” has a prechorus in which the lyrics follow the same pattern but vary a bit each time (the first two prechoruses start with “One small window,” and the third with “One small break”).

Many pop songs skip the bridge and just use a verse-prechorus-chorus form. The prechorus-chorus combo maximizes repetition . . . and makes it so the song is hard to get out of your head even when you dearly wish you could.

Intros, outros, and interludes

In addition to the major sections above, a song may have smaller bits and pieces that add a little variety. At the top might be an intro, which is typically a short instrumental passage—sometimes built from a piece of the chorus or another part of the song. At the end, a song may have an outro (also known, more formally, as a coda). The outro is sometimes an extension of the last chorus, with some kind of development in the melody, harmony, or words.

To cite some songs mentioned above:

“Over the Rainbow” has a coda with the line “If happy little bluebirds fly beyond the rainbow, why oh why can’t I?”

“Eight Days a Week” uses the same up-the-neck guitar riff for its instrumental intro and outro.

In the middle of songs, too, there are often interludes that provide a little breathing room—for instance, between the chorus and the next verse or the bridge. Most commonly an interlude simply repeats the intro. That’s what happens in “Proud Mary,” where the intro chord pattern returns as an interlude after the chorus a couple of times.

The intro in my own “Write Again” is particularly important in holding the song together. The song opens with a short intro melody on guitar and clarinet, which then repeats as an interlude after verse one and again, in a longer version, after verse two; and after the last verse as an outro. In this case the intro melody is distinct from the vocal melody and adds another hook that complements the chorus.

Using song form

These basic components of songs may be familiar to you, but you can learn a lot by paying closer attention to them. When you listen to songs, try identifying the sections. Oftentimes you’ll be able to guess what’s next—for instance, after a verse/chorus, verse/chorus, there’s a good bet a bridge or interlude is coming. It’s also illuminating to notice when songwriters arrange the parts in an unexpected way—you can find structural ideas to try in your own songwriting.

Becoming more conversant with song form gives you an easy shorthand for communicating with other musicians. And in writing, a good sense of structure can provide you with a kind of schematic for a song in progress—that’ll help you figure out how many verses you need, or if the song is too repetitive and could really use a bridge. Now your job is to fill in these sections with the story that wants to be told.